Eight years after the formation of the South Australian colony and just one year after ‘Coppermania’ started at Kapunda, more copper was found at what would become Burra Mine.

In 1845, not one, but two copper deposits were found; one by William Streair and another just after by Thomas Pickett. Due to their close proximity the two finds were grouped together and sold for £1 ($165 now) an acre. However, an ongoing economic crisis meant that few companies could afford this hefty price. Three contenders for the lease arose. The South Australian Mining Association (SAMA), a newly minted cost-book company made up of merchants and landowners, the Mining Association of the Northern Monster Lode and a group of capitalists and pastoralists that for the Princess Royal Mining Company.

None of the companies had the funds to buy the entire lease by themselves, but combined they could. The first two groups joined forces under the SAMA title and with Princess Royal paid half each. The lease was itself divided in two and straws were drawn to determine who would get which end; SAMA won the rights to the northern section which became Monster Lode or Burra Mine and the southern section went to Princess Royal, naming their mine after themselves.

After buying the land, little money was left and lots of financial juggling was required in the early years. This however did not stop the mine from growing exponentially. Since the discovery of copper at Kapunda, hundred’s of Cornish miners began to flock to South Australia and Burra was no exception. The town wasn’t named Burra until much later on, with the Cornish miners setting up smaller settlements, naming them after places from home, like Redruth and Copperhouse.

1947 saw the purchase of the first steam engine as water in the mine became increasingly unmanageable. This was of course ordered from Perran Foundry in Cornwall; this arrived into Port Adelaide two years later and began the 100 mile trip to the mine. Smelters were built at Burra Creek in 1849 by Scheider’s Patent Copper Company. Prior to this all the higher quality ore had to be sent down to Port Adelaide, a journey of two weeks, and then onto Wales for processing. Poor quality ore had been smelted on site since 1947 and the installation meant that all of the ore could be smelted nearby, reducing costs immensely.

The Princess Royal closed in 1851. During this time, gold was found in Victoria and large numbers of miners left to join the rushes and work at the mine ground to a halt. The pumps were turned off and many of the lower levels flooded.

Just three years later, lots of the miners returned and work began again in earnest. Water continued to be a problem and a new larger engine was sought. This was purchased in 1858 and installed two years later. In 1860 the Monster Mine was considered the largest in Australia. However, this did not last and just seven years later underground work had come to a halt. Attention turned to above ground offerings and a new dressing floor with a tower was erected to treat this lower grade ore.

The mine struggled on for several more years, closing in 1877 as copper prices fell. One last attempt at working the site occurred nearly 100 years later in 1970, under Adelaide & Wallaroo Fertiliser Ltd, lasting ten years. Samin Ltd continued to process stockpiled ore on site for several years afterwards. In 1981 the mine closed for good and was later transformed into the heritage site it is today.

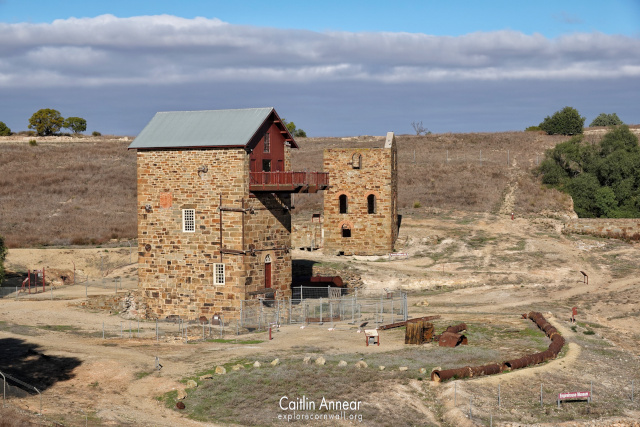

Engine Houses

The first engine house was ordered in the late 1840’s; this came second hand from Perran Foundry and was named after the principle mine captain, who may have worked at Tresavean in Lanner. Installed and working in 1849, it was inactive only three years later. The 50″ engine was dismantled the following year and sold to Bon Accord in 1859 for £2000 ($240,438 now). In 1887 it then went to Bird-in-Hand Mine. A 30″ crusher was added to the mine in 1850. As water became an increasing problem, this also started to pump water in 1855 before being sold to Karkulto Mine the year after.

In 1852, a much larger pumping engine was ordered from Perran Foundry. This was a 80″ engine that worked until 1862 called Schneider’s. A 30″ whim was installed on Peacock’s shaft in 1857. It actually arrived in Australia, again from Perran Foundry seven years prior, but significant delays in building and installing the engine meant it did not go to work when it should have. It was converted to pumping water in 1872 and was scrapped in 1916.

Two engine houses were installed around Morphett’s shaft. The first was a 80″ pumping engine costing £8,688 ($1,058,970 now) erected 1860 by Thomas Paynter and Ambrose Harris, two Cornishmen. It stopped work for two years between 1868 and 1870, before stopping for good in 1877. The engine house caught fire in 1925 and was reconstructed as part of South Australia’s Jubilee 150 celebrations in 1986. A 20″ whim was also installed in 1861 until it was adapted to drive dressing machinery seven years later.

The last pumping engine to be built on the site was Graves. It was erected in 1868 by Thomas Payne. The house was originally supposed to have a new engine from Cornwall, but the order was cancelled and the idle engine in Schneider’s was going to be installed. While the bedstones from Schneider’s were moved into the new house, the engine never made it.

Two further engines were installed later in the mines life. 1876 saw a small horizontal whim being installed to haul ore trucks from the open cut up to the dressing tower and a 22″ crusher in 1874.

Tinline (25 fathoms/46m), Beck (20 fathoms/37m), Penny, Graham Air (50 fathoms/91m), Paxton, Kingstone No 1, Kingston No 2, Ayer No 1 (60 fathoms/110m), Ayer No 2, Stock (35 fathoms/64m), Roach (70 fathoms/128m), Graves, Peacock Main (60 fathoms/110m), Schneider, Peacock Air (40 fathoms/73m), Peacocks Bye (40 fathoms/73m), Waterhouse (70fathoms/128m), Blyth, Morphett (100 fathoms/183m) and Hector (60 fathoms/110m).

1845-77

50,000 tonnes copper, valued at £5 million.

1971-81

24,000 tonnes of copper

Access to the mine on foot is free, although you can pay to drive through the site and to visit the inside of Morphett’s engine.

A large section of the mine is currently closed off to the public due to decreasing ground stability, but all the engine houses can be clearly seen.

Blake, T. (2024). Historical monetary data for Australia. Thom Blake Historian. https://www.thomblake.com.au/secondary/hisdata/query.php

Davies, M. (2003). The South Australian Mining Association: An Early Australian Cost-book Company. Journal of Australasian Mining History, 1(1), 31–50.

Davies, M. (2010). Financing the Burra Burra Mines, South Australia: Liquidity Problems and Resolutions. Journal of Australasian Mining History, 8, 36–62.

Department of Mines and Energy. (n.d.). Signs at Burra.

Drew, G. J., & Connell, J. E. (2012). Cornish Beam Engines in SA Mines (2nd ed.).

Drexel, J. F. (1952). Mining In South Australia. Department of Mines and Energy Special Publications.

Drexel, J. F. (2008). Review Of The Burra Mine Project, 1980–2008—A Progress Report. In Geological Survey Branch, Minerals And Energy Resources. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/34725682/review-of-the-burra-mine-project-1980a2008a-a-progress-misa

Finch, P., & Auhl, I. (1979). Burra in Colour. Investigator Press Pty Ltd.

Nance, D. (2019). Cornish Beam Engines in South Australia: Kapunda, Burra, Wallaroo and Moonta. International Stationary Steam Engine Society, 39(1).

National Trust of South Australia. (2020). Discovering Historic Burra (G. J. Drew, Ed.; 9th ed.). Finsbury Green.

Shute, J. (2013). When is a Store not a Store? When it’s a Smelting House. Journal of Australasian Mining History, 11.